As teenagers we used to gather in my cousin’s basement and watch horror films such as Nightmare on Elm Street (1984-2010) or the Exorcist (1973)–as the disturbing scenes were tattooed onto our psyches. Today mega-hits like the Walking Dead (2010-2015) dominate TV. Why on earth do we go to a movie to be scared?! I never understood why…until now.

Aristotle had a theory on this. In his day people would go to the theater to watch a tragedy. He identified a theme to these tragedies in his book the Poetics (335 BC), which has been used as the standard guide for critical interpretation of tragedy for more than two thousand years. He called it catharsis, the purging of the emotions of pity and fear that are aroused in the viewer.

The effects of simply watching a tragedy were emotionally complex. It’s more than just entertainment. We get a rush when there is adventure and danger, but we also get the peace we need when we suppress these emotions as they rise, because it is “only a movie.”

So the intense emotional stimulus which would normally lead to fear and flight, leads to pleasure instead and we get the rush without the liabilities of that rush–which is in and of itself extremely pleasurable. See more from Psychology Today article on this issue.

Freddy Kruger, Michael Myers, and the whole genera of vampire films feed off this rush within us. The top 10 horror movies of all time all seem to have this in common.

What is it about them even today that attracts and repels us?

David, L. Simpson, writes that:

“Tragedy depicts the downfall of a basically good person through some fatal error or misjudgment, producing suffering and insight on the part of the protagonist and arousing pity and fear on the part of the audience.”

Simpson then breaks down the requirements for a great tragedy:

- A true tragedy should evoke pity and fear on the part of the audience. According to Aristotle, pity and fear are the natural human response to sp

ectacles of pain and suffering–especially to the sort of suffering that can strike anybody at any time. Aristotle goes on to say that tragedy effects “the catharsis of these emotions”–in effect arousing pity and fear only to purge them, as when we exit a scary movie feeling relieved or exhilarated.

ectacles of pain and suffering–especially to the sort of suffering that can strike anybody at any time. Aristotle goes on to say that tragedy effects “the catharsis of these emotions”–in effect arousing pity and fear only to purge them, as when we exit a scary movie feeling relieved or exhilarated.

- The tragic hero must be essentially admirable and good. As Aristotle points out, the fall of a scoundrel or villain evokes applause rather than pity. Audiences cheer when the bad guy goes down. On the other hand, the downfall of an essentially good person disturbs us and stirs our compassion. As a rule, the nobler and more truly admirable a person is, the greater will be our anxiety or grief at his or her downfall.

- In a true tragedy, the hero’s demise must come as a result of some personal error or decision. In other words, in Aristotle’s view there is no such thing as an innocent victim of tragedy, nor can a genuinely tragic downfall ever be purely a matter of blind accident or bad luck. Instead, authentic tragedy must always be the product of some fatal choice or action, for the tragic hero must always bear at least some responsibility for his own doom.

A very insightful analysis of this is this short podcast from Stuff to Blow Your Mind.

Consider psychologist Dr. Glenn D. Walters who identifies many primary factors of the horror film allure. Read his article here if you are interested.

It does not take a genius to remind us to beware what we watch.

We also love horror films not just because it produces strong emotional responses, but because those responses work to build stronger relationships and memories. When we’re happy, or afraid, we’re releasing powerful hormones, like oxcytocin, that are working to make these moments stick in our brain. So we’re going to remember the people we are with. If it was a good experience, then we’ll remember them fondly and feel close to them, more so than if we were to meet them during some neutral event. Shelley Taylor discussed this in her article: Tend and Befriend: Biobehavioral Bases of Affiliation Under Stress.

What is the Christian to do with horror movies? Brian Godawa, screenwriter wrote the following about this:

Horror and thriller movies are two powerful means of arguing against the moral relativism of our postmodern society. Not only do they tend to reinforce the doctrine of the basic evil nature in humanity, but they can personify profound arguments of the kind of destructive evil that results when society denies absolute morality. Of course, this is not to suggest that all horror movies are morally acceptable. In fact, I would argue that many of them have degenerated into immoral exaltation of sex, violence and death. A good example of this exploitation is the heroic status that has been given to Hannibal Lecter. So much so, that the sequel, Hannibal, was written with the villain as hero, indeed as a Christ figure. And it would be vain to try to justify the unhealthy obsession that some people have with the dark side, especially in their movie viewing. Too much focus on the bad news will dilute the power that the Good News has on an individual. Too much fascination with the nature and effects of sin can impede one’s growth in salvation. So, the defense of horror and thriller movies in principle should not be misconstrued to be a justification for all horror and thriller movies in practice. It is the mature Christian who, because of practice, has his senses trained to discern good and evil in a fallen world. It is the mature Christian who, like the Apostle Paul, can expose himself to his culture and draw out the good from the bad in order to interact redemptively with that culture (Acts 17).

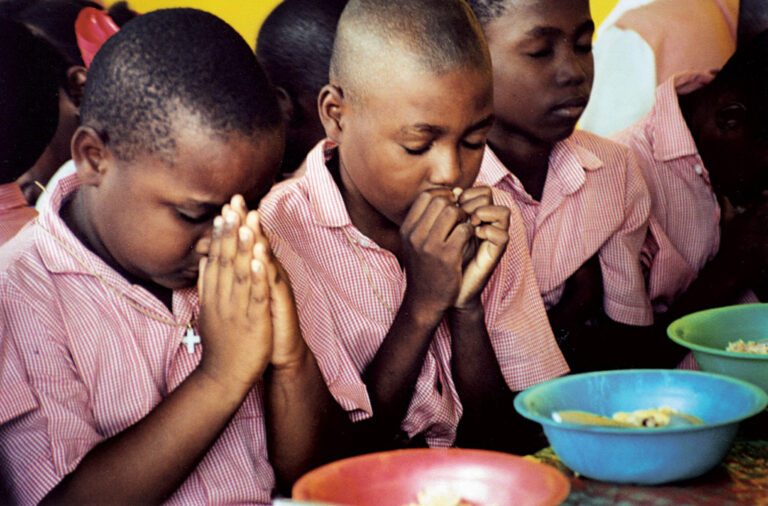

So then, to be image bears of God, or imago Dei’s we need to beware what we watch, and when confronted with evil, either on the screen or in life, be prepared to explain how evil is real and if evil is real, there must be a real good, and if there is a real good, then there must be a real Moral Law Maker who made it so.

What do you think?

Pingback: Absolute Evil | Logically Faithful

Pingback: Speaking with the Devil | Logically Faithful

I would have to say that i agree with your article, in fact i once wrote an essay partially explaining how horror movies let people experience scenarios without being in actual danger, so i understand the catharsis from viewing them. I would say Simpson’s view on tragedy greatly explains my own

distaste for senseless horror movies. The movies with unlikable teenagers that only serve to infuriate me towards them and hope they die soon. Granted I personally would never wish death on anyone, but when someone in fiction is designed solely to grate on ones nerves and be as despicable as possible and is meant to be the protagonist, then i find it very difficult to hope they somehow survive the terror. That being said I do genuinely begin to miss horror movies with likable protagonists that genuinely made me sad when they were slaughtered. One of the Friday the 13th films had characters like that and it was perhaps one of the few times i was genuinely sad that characters were butchered in a horror movie. Another example would be the original Alien, with its characters feeling like real people.